Animal Protein and Poison: The Hidden Science Behind What We Eat

Learn how to enjoy animal protein safely and discover its benefits, risks, gut impact, and practical tips for long-term health and vitality.

HEALTH & AWARNESS

Tapas Kumar Basu

12/27/20257 min read

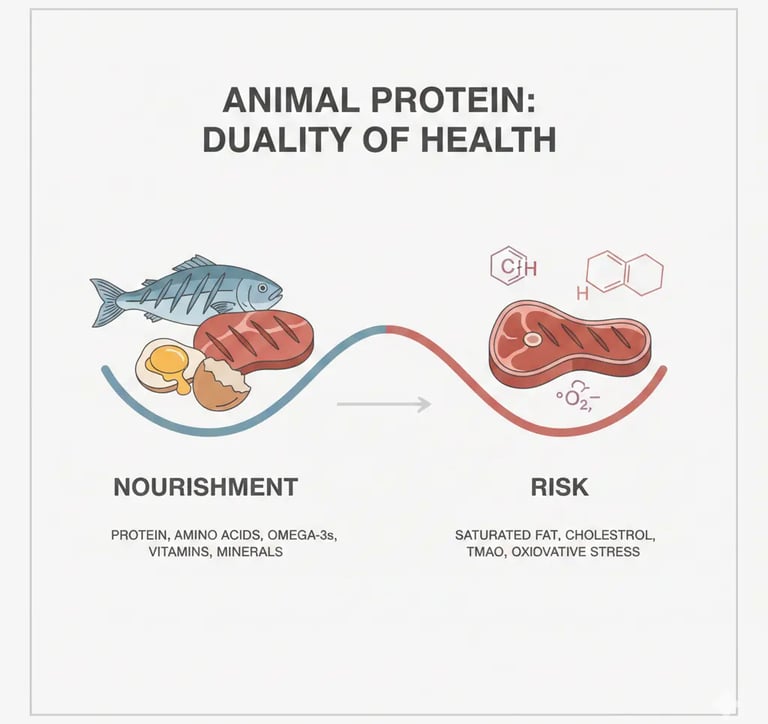

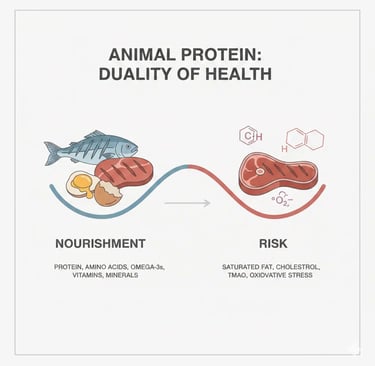

Animal protein has been celebrated, feared, defended, criticized, glorified, and sometimes demonized. In modern nutrition, few topics generate as much discussion as whether animal protein is a source of nourishment or a source of toxicity. Millions of people include meat, eggs, and dairy in their diets. Scientific research, however, increasingly reveals a complex picture. Animal protein nourishes the body, yet it can also produce biochemical compounds that behave like toxins, irritants, or inflammatory agents.

This article does not aim to terrify or moralize. It takes a calm, scientific, and human approach to explain what really happens in the body when animal proteins are broken down. It explores how certain compounds, such as hydrogen sulfide, heterocyclic amines, trimethylamine N-oxide, ammonia, advanced glycation end products, and nitrosamines, are formed during cooking, digestion, and metabolism. Most importantly, it explains what these compounds mean for long-term health and how a person can make intelligent dietary choices without falling into extremes. This is the science of animal protein unmasked, explained, and made meaningful.

1. Understanding Animal Protein: Healthful or Harmful?

Animal protein, found in meat, eggs, fish, dairy, and poultry, is rich in essential amino acids, vitamin B12, heme iron, creatine, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids. These nutrients are vital for growth, immunity, muscle function, and metabolic health. No responsible scientific discussion denies these benefits.

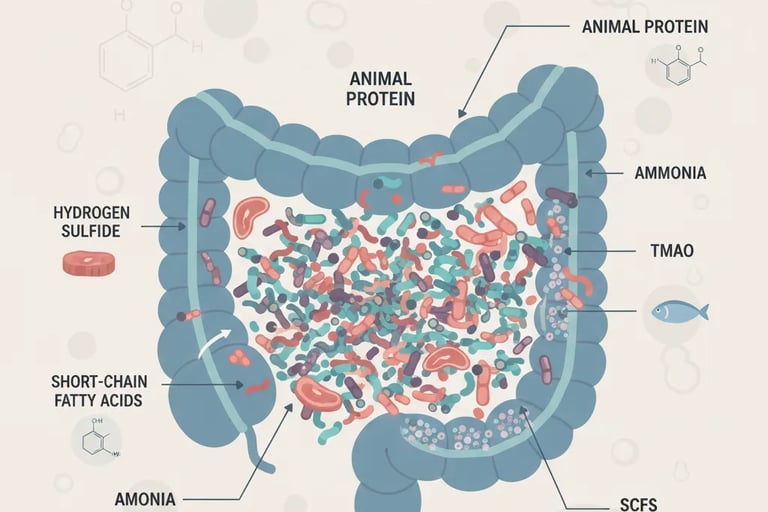

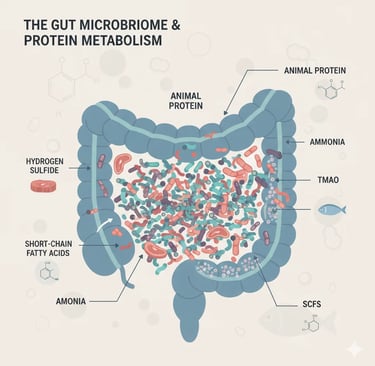

The human body is not a simple machine. It is an ecosystem, a living chemistry lab where every molecule has consequences. The digestive tract hosts trillions of microbes, each capable of turning food into healing compounds or toxic by-products. When animal protein enters this ecosystem, several biochemical reactions begin. Some are helpful, some can be harmful, and some become harmful only when consumed in excess. Understanding these reactions is the key to making wise health decisions.

2. What Happens When Animal Protein Enters the Gut

Animal protein begins breaking down in the stomach under hydrochloric acid and pepsin. More important reactions occur later in the large intestine, where gut bacteria ferment the remnants that were not fully digested in the small intestine.

Unlike plant fiber, which beneficial bacteria ferment into healthy short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate, leftover animal protein is decomposed by putrefactive bacteria that produce different chemicals. Many of these chemicals are potentially toxic. Major by-products formed from animal protein include:

Hydrogen sulfide (H₂S)

Ammonia

Indoles and phenols

p-cresol

Trimethylamine, which is converted to TMAO

Polyamines such as putrescine and cadaverine

These compounds are not always harmful. For example, hydrogen sulfide plays signaling roles in cells. Excessive amounts, however, can irritate the gut lining, disrupt microbiome balance, and increase systemic inflammation.

3. Hydrogen Sulfide: A Toxic Paradox

Many readers ask whether meat produces hydrogen sulfide in the digestive system. The answer is yes. Animal proteins rich in sulfur-containing amino acids, such as methionine and cysteine, are broken down by gut bacteria into hydrogen sulfide gas.

Hydrogen sulfide has dual roles. In small amounts, it acts as a signaling molecule. In larger amounts, it damages the intestinal barrier and contributes to leaky gut. It interferes with the energy metabolism of colon cells, impairs butyrate oxidation, and encourages inflammation in the gut. Excess hydrogen sulfide is associated with:

Ulcerative colitis

Irritable bowel syndrome

Colon irritation

Microbial dysbiosis

Reduced short-chain fatty acid production

This does not mean animal protein is automatically harmful. Excess, especially without fiber, encourages sulfur-reducing bacteria to produce higher levels of hydrogen sulfide. This balance is the real determinant of health outcomes.

4. Cooking Meat and the Formation of Toxic Compounds

Animal protein can also become harmful before we eat it. High-heat cooking alters the chemical structure of amino acids and fats. The higher the temperature, the more these transformations occur. Major toxic compounds formed during cooking include:

4.1 Heterocyclic Amines

Heterocyclic amines form when amino acids react with creatine and sugars at high temperatures. These compounds are mutagenic and can damage DNA. The risk increases with cooking temperature and duration.

4.2 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons form when fat drips onto flames during grilling or barbecuing. Smoke carries these compounds and deposits them onto the meat. They are linked with genetic mutations and long-term inflammatory changes.

4.3 Advanced Glycation End Products

Advanced glycation end products form when proteins and fats react with sugars at high temperatures. They accumulate in tissues and are associated with insulin resistance, vascular stiffness, kidney stress, and accelerated aging.

4.4 Nitrosamines

Processed meats such as sausages, bacon, and ham often contain nitrates and nitrites. These compounds can react with amino acids to form nitrosamines during cooking. Nitrosamines are strongly associated with gastrointestinal cancers. This explains why health authorities classify processed meats as carcinogenic and red meat as probably carcinogenic when consumed in excess.

5. Metabolites Formed Inside the Body After Eating Animal Protein

The digestive system produces several internal chemicals from animal protein. Some are harmless, and others influence long-term health.

5.1 Trimethylamine and TMAO

Red meat and eggs contain choline and carnitine. Gut bacteria convert these nutrients into trimethylamine, which the liver then converts into trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). High TMAO levels are associated with cardiovascular disease, platelet activation, and kidney strain.

5.2 Ammonia

Amino acids contain nitrogen. When they break down, nitrogen is released as ammonia. The liver converts ammonia into urea for excretion. Excess ammonia in the gut can irritate the intestinal lining and affect microbial balance.

5.3 Polyamines

Polyamines such as putrescine and cadaverine are produced when proteins break down in the colon. These compounds are associated with unpleasant odors and gut irritation. Research continues to explore their role in cell growth and tumor formation. Repeated accumulation over years may influence chronic inflammation, gut dysbiosis, and metabolic imbalance.

6. The Microbiome: The Real Judge of Animal Protein

The microbiome determines whether animal protein behaves like food or poison. A healthy and diverse microbiome digests protein efficiently. It prevents excessive toxin formation, neutralizes harmful compounds, and protects the gut lining.

A disturbed microbiome struggles with protein digestion. Harmful bacteria grow, and toxic by-products increase. Modern lifestyle factors such as low fiber diets, stress, poor sleep, sugar-rich foods, and processed foods weaken the microbiome. When a weak microbiome meets high quantities of animal protein, health problems are more likely.

The solution is not to avoid meat completely. The solution is to strengthen the microbiome with fiber-rich foods, fermented foods, whole grains, legumes, fruits, vegetables, and herbs. These foods reduce toxin production and support beneficial bacteria.

7. Benefits of Animal Protein in Proper Context

Animal protein supports muscle development, hormone balance, immunity, and energy production. It contains essential nutrients that are difficult to obtain from plant foods alone. Fish is particularly beneficial because it contains omega-3 fatty acids that reduce inflammation.

Harm arises from imbalance. Excess meat, low fiber intake, processed food, and high heat cooking create conditions for toxin formation. Traditional diets included meat, vegetables, herbs, and grains. This balance allowed the body to enjoy protein benefits without suffering from toxic by-products.

8. Practical Ways to Reduce Toxin Formation

There are several ways to enjoy animal protein safely.

Cook gently: Steaming, stewing, boiling, poaching, and slow cooking minimize toxin formation. Avoid charring, frying, or excessive browning.

Pair meat with fiber-rich foods: Vegetables, whole grains, and legumes reduce hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and TMAO formation.

Limit processed meats: These contain the highest levels of toxic compounds.

Maintain microbiome diversity: Eat fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, lentils, fermented foods, and herbs.

Moderate portion sizes: Most people consume more protein than needed.

Rotate protein sources: Include plant-based proteins to protect gut health and reduce toxin formation.

Conclusion or Final Thoughts

Animal protein is a powerful source of nourishment but must be consumed with understanding. It can strengthen the body or irritate it depending on cooking methods, portion size, and the rest of the diet. The real poison is not the protein itself but imbalance. Adequate fiber, antioxidants, and plant-based foods keep toxic by-products low. Knowledge allows food to become medicine. Ignorance turns the same food into potential harm. Understanding the science of animal protein, gut microbiome, cooking methods, and long-term health allows us to enjoy animal protein as a source of strength rather than poison.

FAQs: Animal Protein and Your Health

1. Is all animal protein bad for me?

Absolutely not. Animal protein is packed with essential amino acids, vitamin B12, heme iron, and other nutrients that support muscles, immunity, and overall vitality. The problem arises when meat or eggs are overconsumed, cooked too hot, heavily processed, or eaten without enough fiber and plant foods. In moderation and with balance, animal protein is very much beneficial.

2. How does animal protein create “toxic” compounds in the gut?

When some animal protein reaches the large intestine undigested, certain gut bacteria break it down in a process called putrefaction. This can produce hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, indoles, and polyamines. Small amounts are harmless, but too much can irritate the gut lining, upset your microbiome, and contribute to inflammation over time.

3. What cooking methods are safest for meat?

Gentle is best. Steaming, boiling, poaching, slow cooking, or stewing reduces the formation of harmful compounds. Avoid charring, frying, and high-heat grilling, which create substances like HCAs, PAHs, AGEs, and nitrosamines that can affect long-term health.

4. Can a healthy gut microbiome protect me from toxins?

Yes! A strong, diverse microbiome can handle moderate amounts of animal protein, neutralize harmful compounds, and support gut health. Eating fiber-rich foods, fermented foods, herbs, and a variety of plant proteins strengthens the microbiome and helps keep toxin production in check.

5. How can I enjoy animal protein safely?

Focus on balance. Eat moderate portions, pair meat with vegetables, grains, or legumes, choose fish and eggs over red or processed meats, use gentle cooking methods, and rotate with plant-based proteins. This way, you get the benefits of animal protein without triggering excess toxic by-products.

6. Does the type of animal protein matter?

Yes. Fish is often the healthiest due to omega-3 fatty acids, while red and processed meats generate more compounds linked to inflammation and long-term health risks. Eggs and dairy are generally safe in moderation but should be paired with fiber-rich foods for best digestion.

7. Can I completely avoid the risks of animal protein?

Not entirely—but you can minimize them. Combining moderate portions, gentle cooking, plant-based foods, and a healthy microbiome dramatically reduces the formation of harmful metabolites. The goal isn’t fear—it’s knowledge, so you can enjoy protein wisely.

Explore fitness, meditation, and healthy living tips.

© 2025. All rights reserved.